Can riding a bike without a helmet actually be safer?

I came across PedalMe cargo bike company last year, and was impressed. It provides a last-mile cargo and passenger ebike service. All of its riders are employed full-time, with pre-scheduled shifts and hourly pay (instead of the per-delivery income in the gig economy model).

Sounds pretty good, hey? But there’s a quirk — their riders are not allowed to wear bike helmets.

According to the company’s latest newsletter:

We ban our staff from wearing helmets for risk management and safety reasons because of something called “Risk Compensation” — whereby those wearing protective gear take greater risks and therefore have more collisions.

They further expanded these ideas on Twitter:

People that are taking risks that are sufficient that they feel they need to wear helmets are not welcome to work for us – because our vehicles are heavy and could cause harm, and because we carry small children on our bikes.

Instead – we systematically work to reduce risk.(1/n)

— Pedal Me (@pedalmeapp) February 4, 2022

Pedal Me has in-house cycling instructors and a thorough training program. They contend that this and the composition of their bikes means that riders are much less likely to have collisions where helmets will help them.

Instead, they focus on “systematically tackling risk through data collection and data-driven decision making.”

Do they save lives?

Well, it depends on who’s asking and who you ask.

Helmets are made of hard plastic and lined with foam, to state the obvious.

If your head makes contact with a hard object like the ground or a pole, they reduce the force of impact to the skull. However, this is less effective when riding at speed.

Of course, to be effective, a helmet needs to be well fitted. There’s also the problem of counterfeit helmets made in China that come with a local safety sticker but lack the safety benefits.

So the pro-helmet stance holds that they reduce the risk of serious head injury or death.

By comparison, a company like PedalMe subscribes to an idea called Risk Compensation.

This is a school of thought in safety where those wearing protective gear take greater risks and therefore have more collisions. For example, this would posit that those wearing seat belts drive more recklessly than those without.

This approach also looks at the idea of social health. It asks whether the safety aspect of helmets outweighs the health benefits of cycling because helmet laws deter people from taking up cycling.

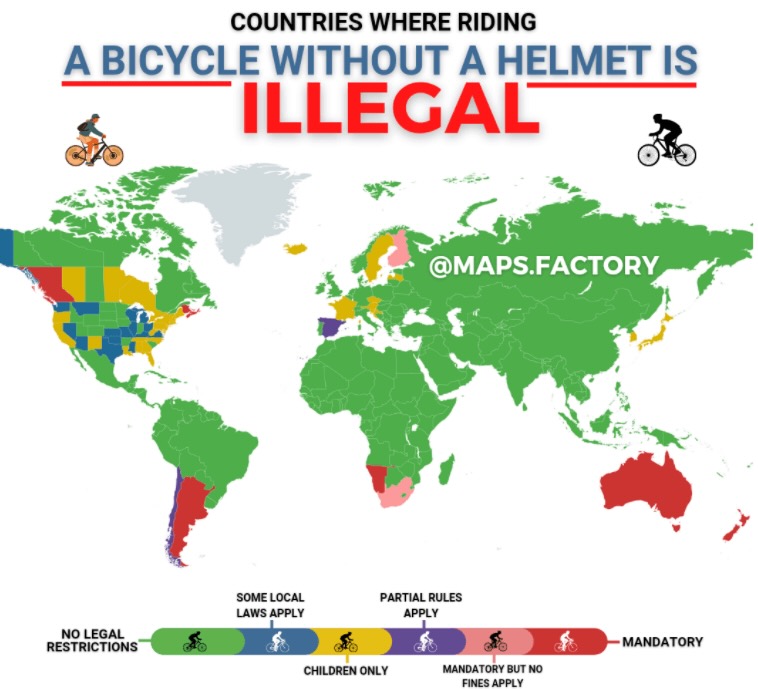

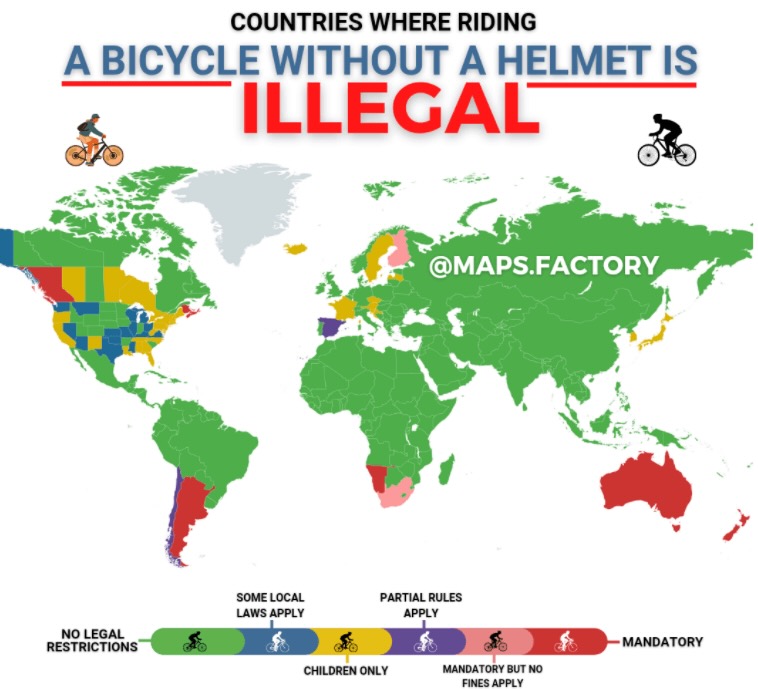

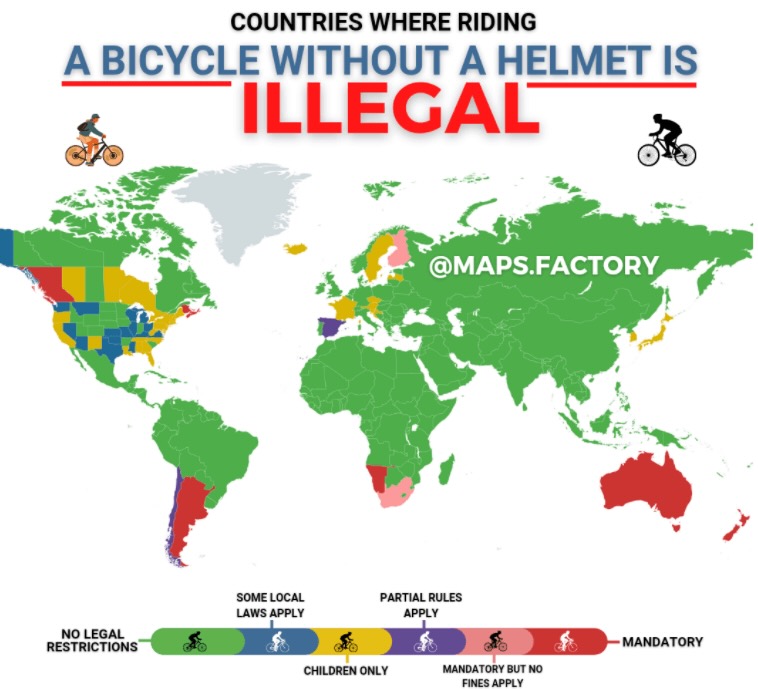

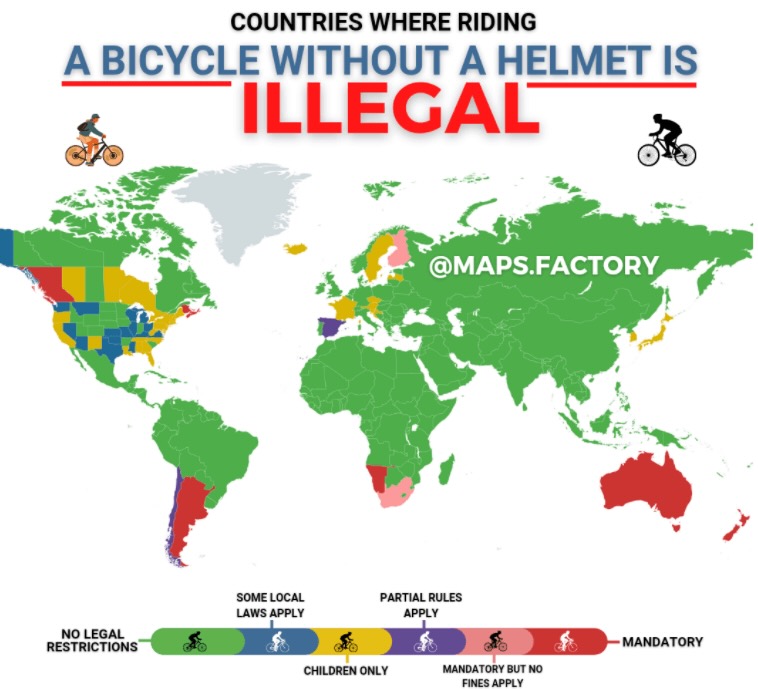

Where are bike helmets legally required?

Bike helmets are completely mandatory in only a few countries, including Argentina, Finland, Sweden, Namibia, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

And it’s downright confusing in Canada and the US, where laws differ on a local level, according to the state, the city, and the rider’s age.

Last week, Seattle city officials overturned the helmet requirement in response to discriminatory enforcement of the rule against homeless people and people of color. The city of Tacoma had previously repealed the requirement in 2020 due to similar concerns.

The city of Tacoma, Washington, repealed its requirement in 2020, citing similar equity concerns.

What’s it like living somewhere with compulsory helmets?

The idea of not wearing a bicycle helmet seemed really alien to me when I moved to Germany from Australia in 2014.

I find that there are massive differences between Australia and Europe regarding bike safety. When I learned to ride a bike, people told me, “Ride like the car drivers are trying to kill you and stay on the footpath as much as possible.”

The reality is that there is a huge culture of disrespect and antagonism towards cyclists in Australia. We also have poorer quality roads and fewer bike lanes.

There’s little effort to police or prosecute drivers who open their car doors on riders, or drive unsafely around bikes.

And, significantly, unlike places like Berlin and Amsterdam, few drivers are cyclists themselves.

Helmets are a barrier to micromobility success

In 2014 the city of Dallas removed the requirement for people aged 18 and older, as a means of encouraging more bike-sharing. And it worked. Compulsory helmets make it harder to introduce a cycling culture.

For example, in Australia,

And yes, you needed a helmet. You could buy one cheaply at a nearby 7/11 convenience store for $3.60 ($5 AUD), but these spontaneous rides became difficult when there were no shops nearby.

Incidentally, it’s the same for the current escooters in Australia, but the helmet comes locked to the escooter. A friend told me, “I haven’t got lice yet, fingers crossed!” So maybe, there’s hope yet.

Just for some bang for your buck, I’m going to show you some rather embarrassing and hilarious helmet ads from my childhood:

This one’s got a kinda metaverse meet Second Life vibe:

Apologies for the quality. I suspect the owner ripped them from a VHS cassette….