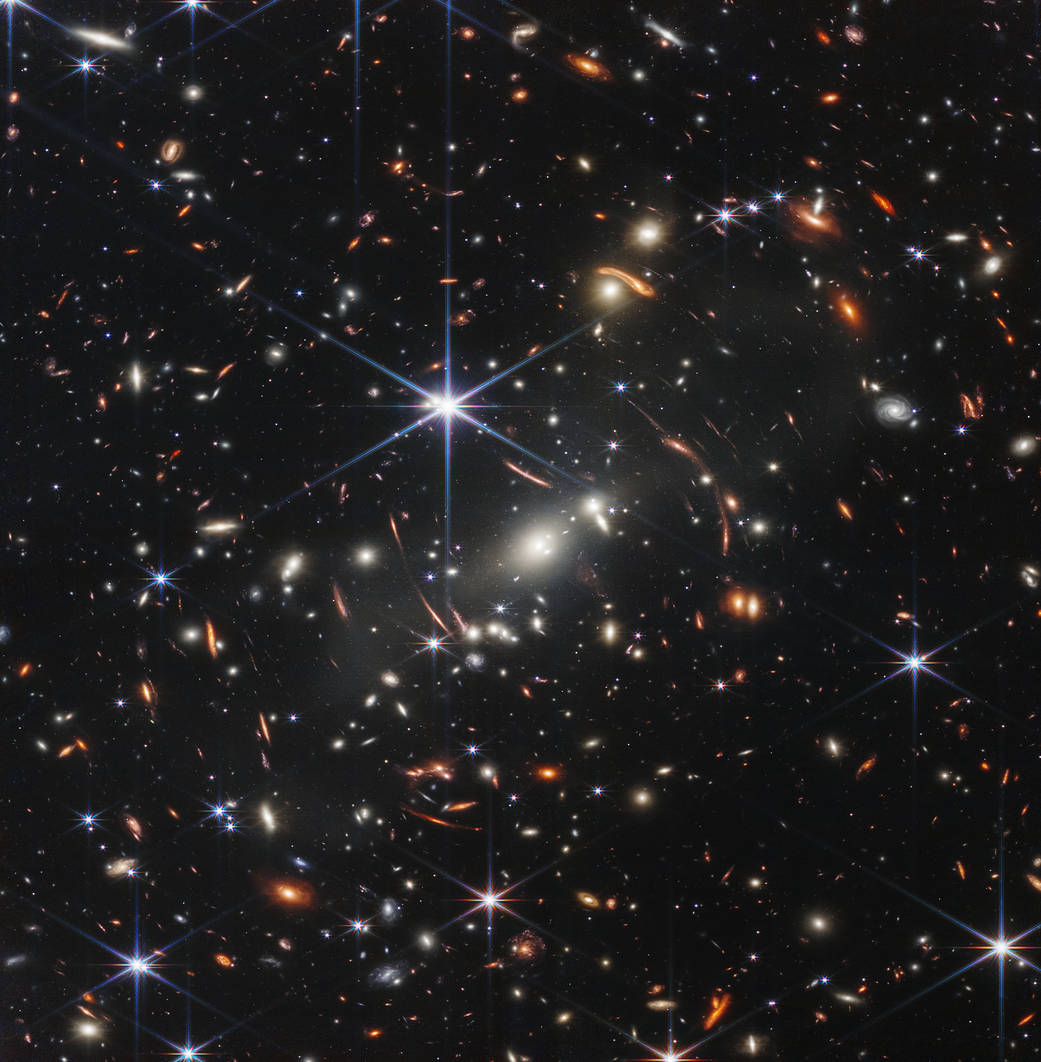

Here are the first full-color images from the James Webb Telescope

On Friday, NASA released the first full-color image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — the largest and most powerful telescope ever launched into space.

Thanks to its massive mirror and the ability to see at the infrared part of the spectrum, it can look back billions of years to capture the faint, red-shifted light from the very beginning of the universe.

Known as Webb’s First Deep Field, the image didn’t disappoint. According to the agency, it’s the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the early, distant universe to date.

It shows the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago.

As per NASA, the combined mass of this galaxy cluster acts as a gravitational lens, magnifying much more distant galaxies behind it — which were brought into sharp focus by the telescope.

Thanks to JWST’s sharpness, researchers were able to identify elements as well: oxygen, hydrogen, and neon.

This makes SMACS 0723 the most distant galaxy cluster that we have this kind of detailed information about.

On Tuesday, we got an awe-inspiring front row seat to cutting-edge space exploration, as NASA revealed four more breathtaking images from the telescope:

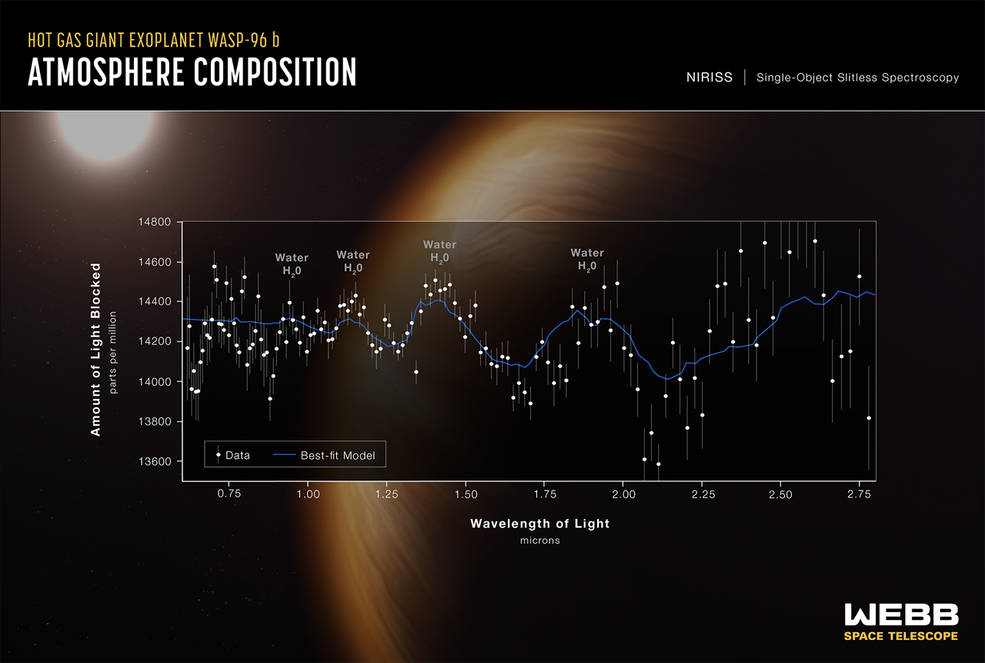

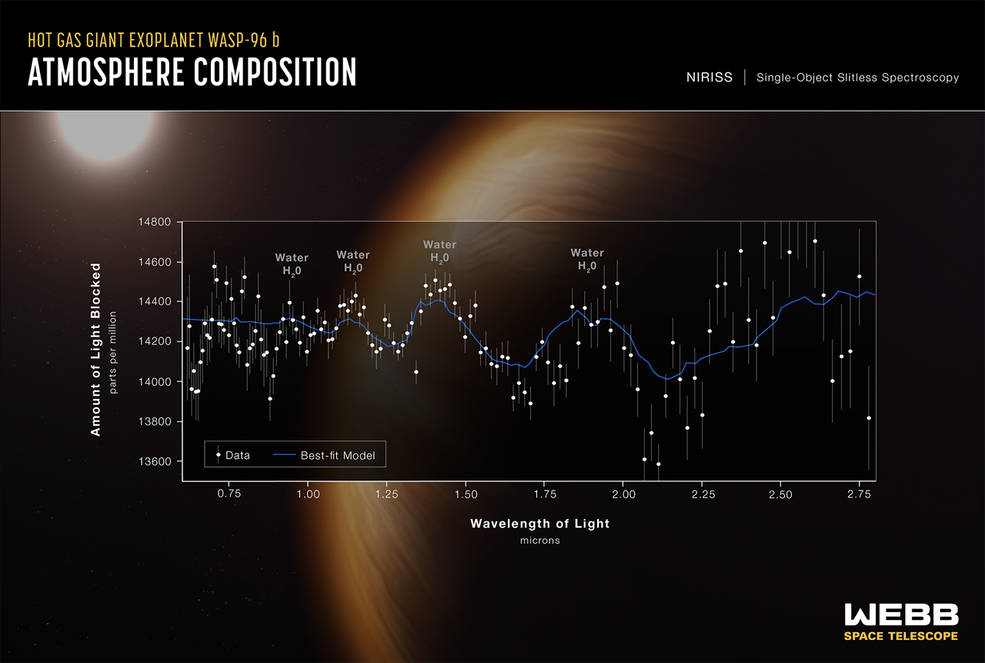

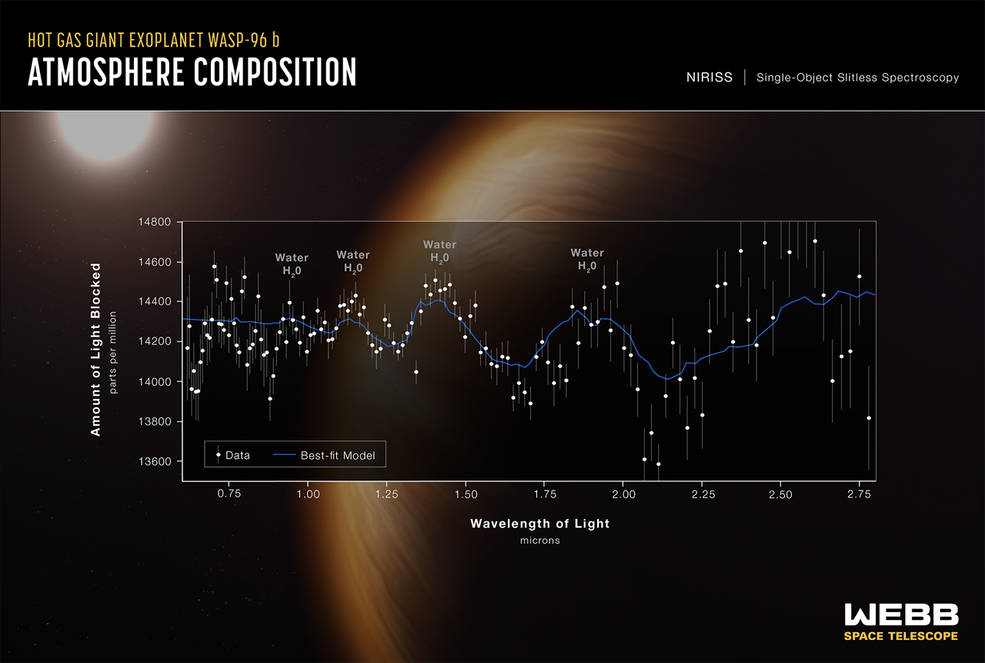

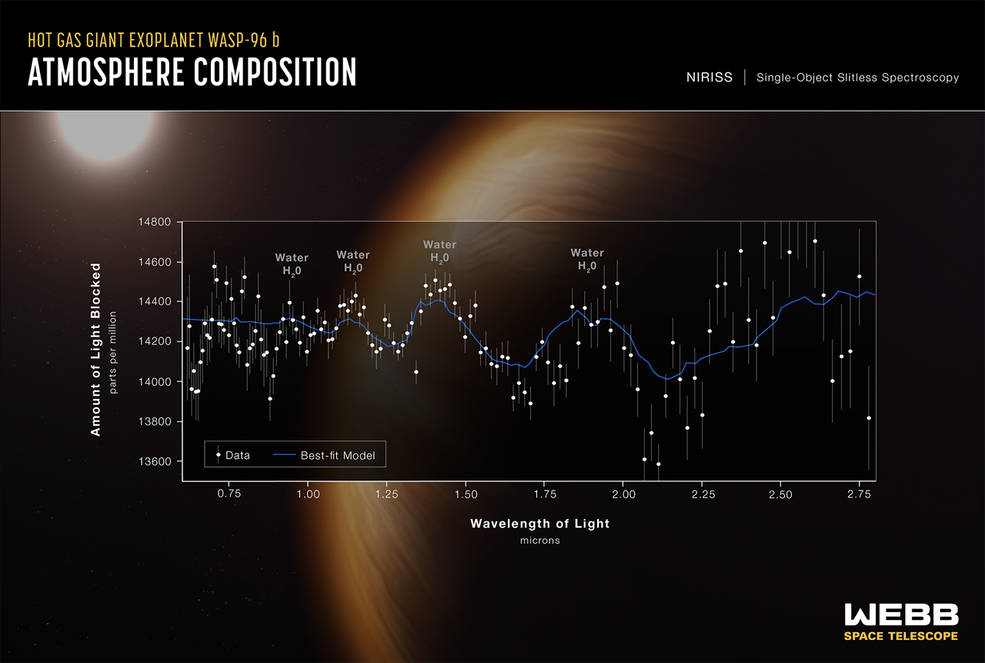

WASP-96 b

WASP-96 b is a giant planet outside our solar system, composed mainly of gas. It’s located nearly 1,150 light-years from Earth, orbiting around a Sun-like star.

The planet is about the same size as Jupiter, but half its mass.

This image doesn’t depict the planet itself, but demonstrates Webb’s unprecedented ability to analyze atmospheres hundreds of light-years away.

Web measured light from the WASP-96 system for 6.4 hours as the planet moved across the star.

The result is a light curve showing the overall dimming of starlight during the transit, and a transmission spectrum revealing the brightness change of individual wavelengths of infrared light — shown in the image above.

Among the most notable findings are the distinct signature of vaporized water, and the evidence of clouds and haze.

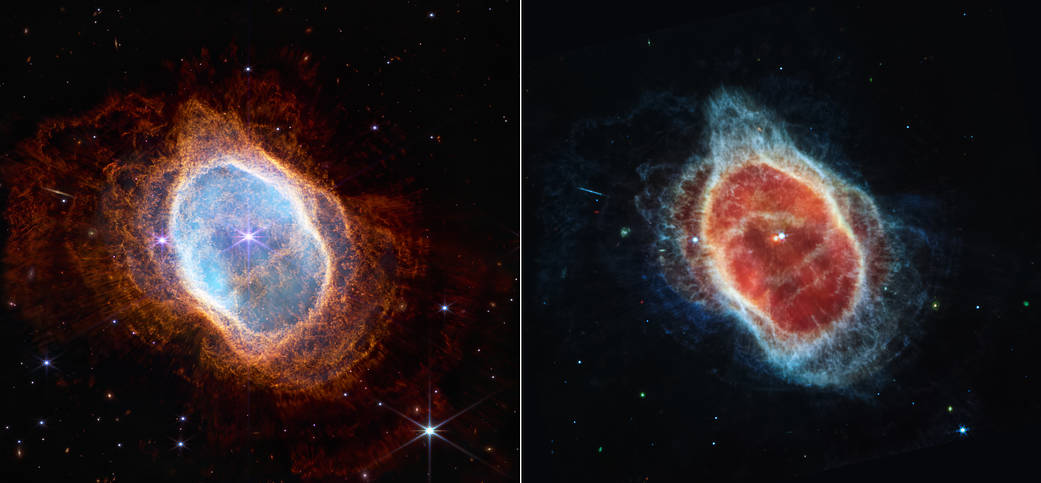

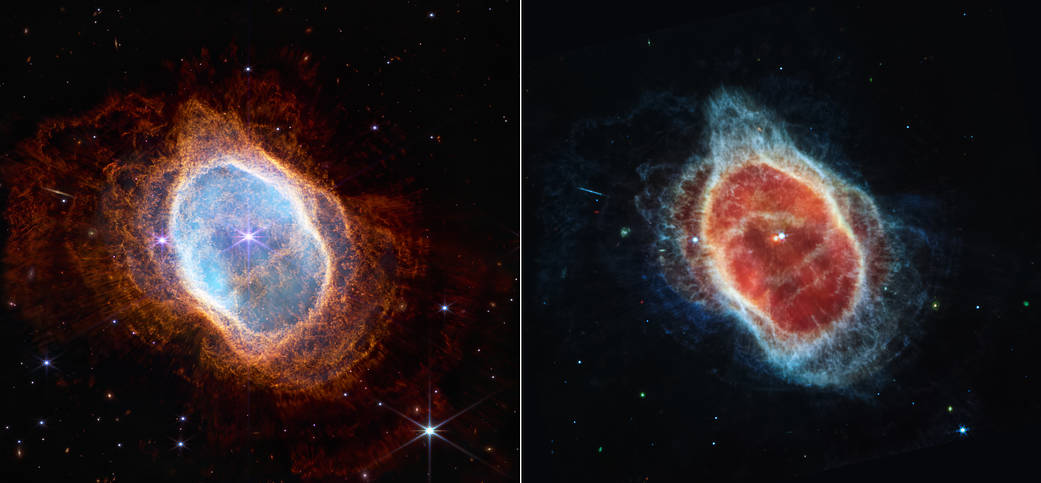

Southern Ring Nebula

This is a planetary nebula — an expanding cloud of gas, surrounding a dying star. It’s nearly half a light-year in diameter, and is located approximately 2,000 light-years away from Earth.

Two stars, which are locked in a tight orbit, shape the local landscape that you can see above.

The stars — and their layers of light — are prominent in the image from Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) on the left. On the right, the image from Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) shows for the first time that the second star is surrounded by dust.

The brighter star is in an earlier stage of its stellar evolution and will probably eject its own planetary nebula in the future. It’s also the one that influences the nebula’s appearance.

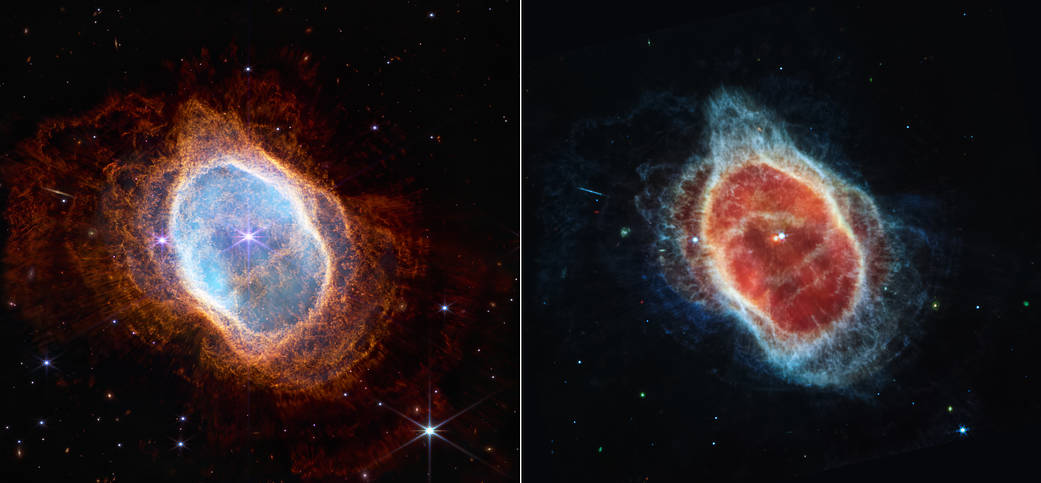

Stephan’s Quintet

About 290 million light-years away, Stephan’s Quintet is a group of five galaxies, located in the Pegasus constellation. It’s notable for being the first compact galaxy group ever discovered in 1877.

This enormous mosaic is Webb’s largest image to date, covering about one-fifth of the Moon’s diameter. It contains over 150 million pixels and is constructed from almost 1,000 separate image files.

The telescope also pierced through the shroud of dust surrounding the nucleus of the group’s topmost galaxy to reveal hot gas near the active black hole and measure the velocity of bright outflows. It saw these outflows driven by the black hole in a level of detail never seen before.

This information should provide new insights into how galactic interactions may have driven galaxy evolution in the early universe.

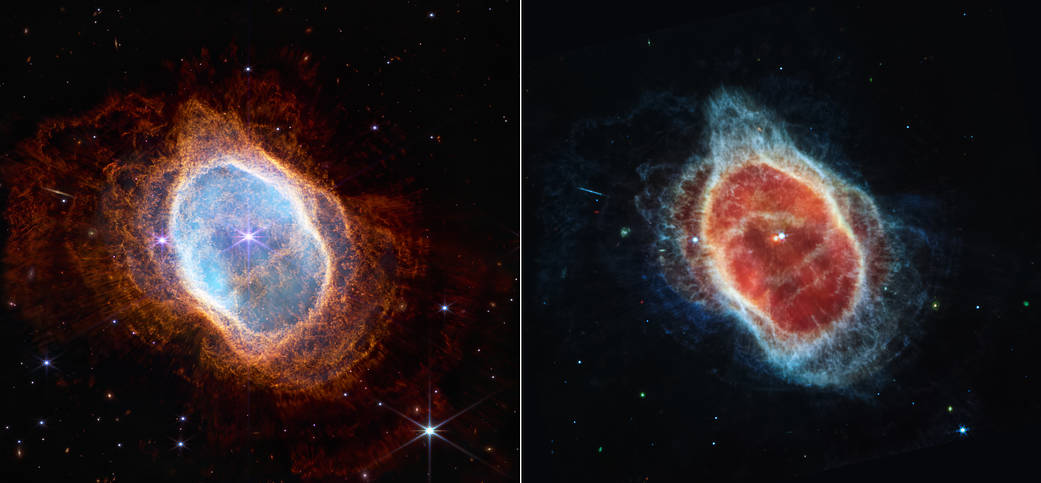

Carina Nebula

Carina Nebula is one of the largest and brightest nebulae in the sky, located approximately 7,600 light-years away. It’s home to many massive stars that are several times larger than the Sun.

The telescope’s 3D picture that you can see above, is the edge of the giant, gaseous cavity within NGC 3324 — a star-forming region within the nebula.

This cavernous area has been carved from the nebula by the intense ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from extremely massive, hot, young stars, which are located in the center of the bubble, above the area shown in this image.

Webb has managed to pierce through cosmic dust, identify emerging stellar nurseries never seen before, and, in turn, shed further light into how stars are born.

Overall, these images aren’t just breathtaking. The JWST shows the potential to unravel the mysteries of early universe formation and with that, of our existence.