The Dutch pioneered lab-grown meat. Why can’t they eat it?

My cravings for meat are well-known to regular readers (hi mum!). But as a self-righteous vegetarian, I refuse to dine on murdered animals. Those beliefs, however, are now being challenged by a heretic: cultivated meat.

Cultivated meat, also known as cultured meat, brings the farm to the lab. Cells are collected from an animal, grown in vitro, and then shaped into familiar forms of edible flesh.

Industry advocates proffer myriad benefits — and needs. According to the UN, around 80 billion animals are slaughtered each year for meat. This livestock produces an estimated 14.5% of global greenhouse gasses, grazes across 26% of Earth’s terrestrial surface, and uses 8% of global freshwater.

Population growth will eventually make these numbers unsustainable.

Cellular agriculture, argue its supporters, can dramatically allay the damage. The produce can satisfy our need for protein (and desire for meat), reduce our carbon footprint, and prevent animal suffering.

CE Delft, an independent research firm, estimates that cultivated meat could cause 92% less global warming and 93% less air pollution, while using 95% less land and 78% less water.

The nascent sector could also become big business. Consulting firm McKinsey predicts the market for cultivated meat could reach $25 billion (€26 billion) by 2030.

It’s not like meat — it is meat.

The sector has developed rapidly since the world’s first lab-grown burger was unveiled in 2013. The patty cost an eye-watering $330,000 to produce. Chefs described it as edible, but not delectable.

One of the scientists behind the project was Daan Luining. The affable Dutchman went on to found Meatable, a cultivated meat startup based in Delft. The company claims its produce is identical to traditional meat.

“It’s not like meat — it is meat,” Luining tells TNW.

After the hamburger launch, Luining tried to turn his own research on cellular agriculture into a business. His big idea emerged from a meeting with Mark Kotter, a neurosurgeon at Cambridge University.

Kotter was demonstrating a breakthrough approach to reprogramming human stem cells. Luining suggested applying the technique to a new target: pork and bovine cells.

He quickly convinced Kotter that cultured meat could have enormous value. In 2018, the duo teamed up with Krijn de Nood, a former McKinsey consultant, to co-found Meatable — and bring their concept to the market.

The meat lab

My previous forays into fake meat were plant-based. I’ve sampled a smorgasbord of the produce, from the McDonald’s McPlant burger to Juicy Marbles’ vegan filet mignon. They were admirable imitations, but there always were cracks in the illusion — and the copious sodium couldn’t hide them.

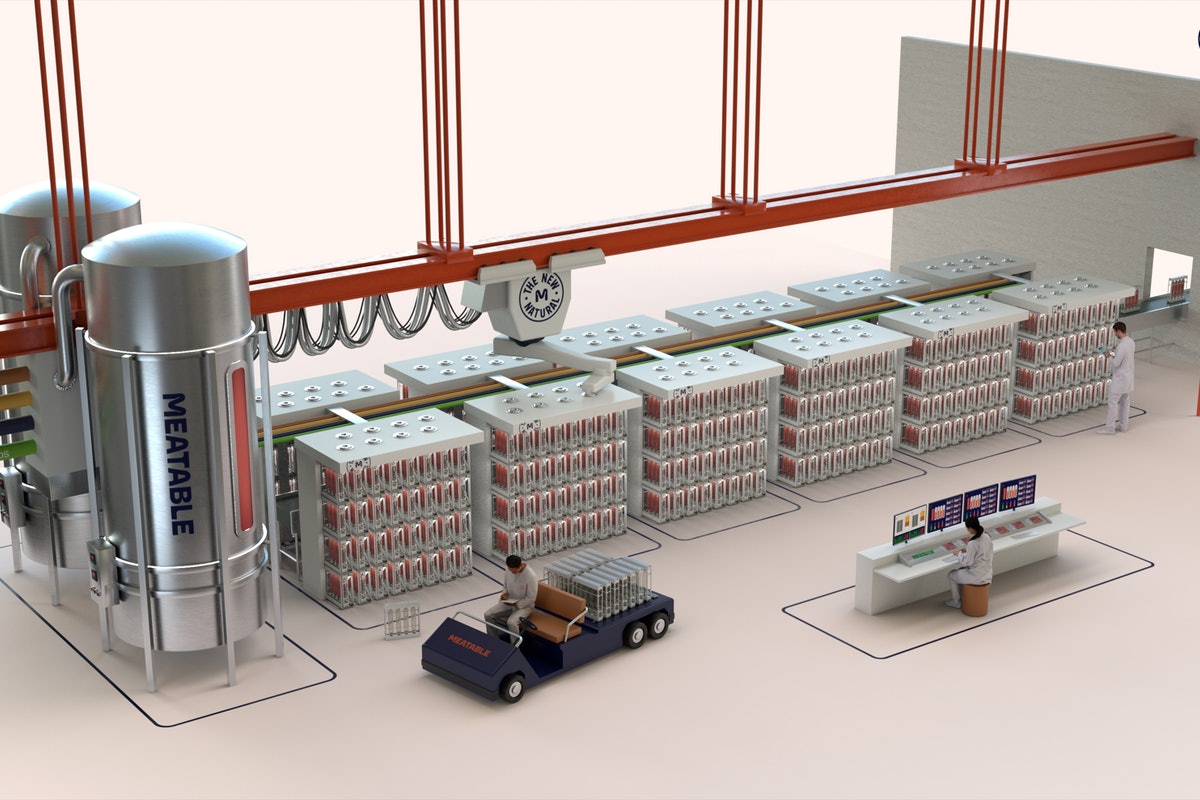

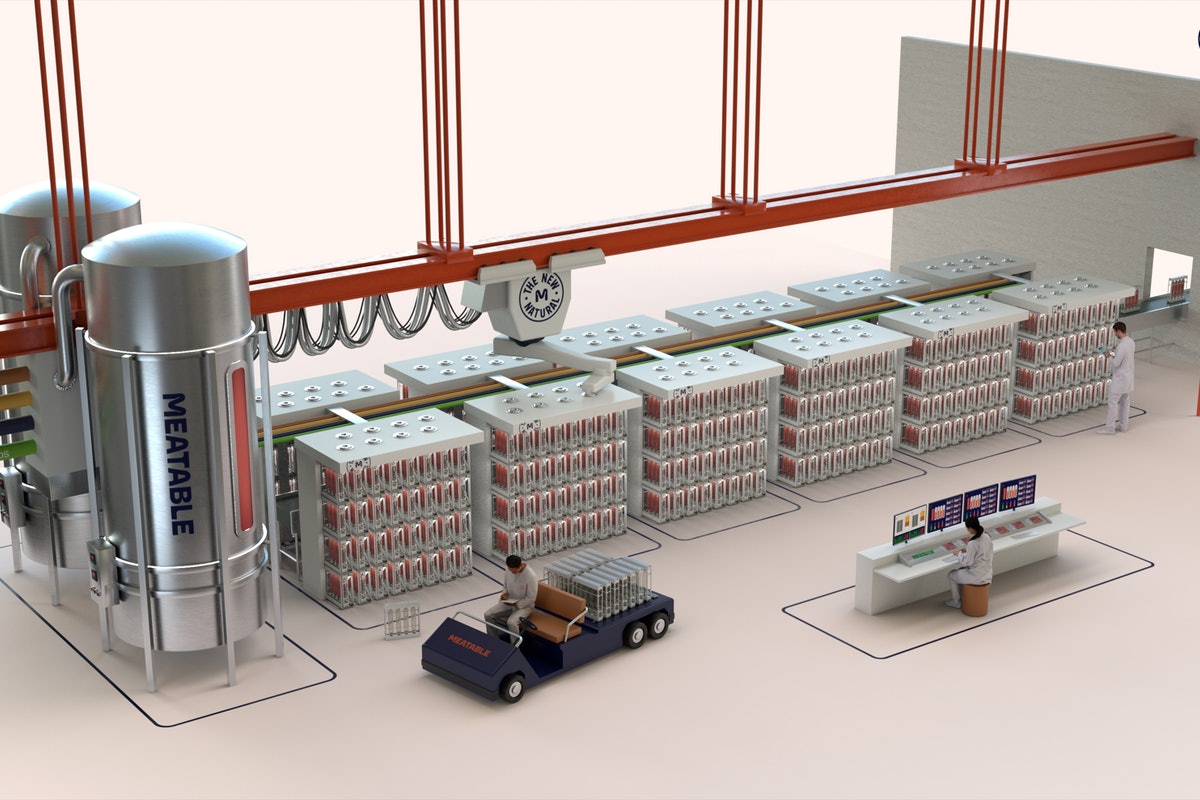

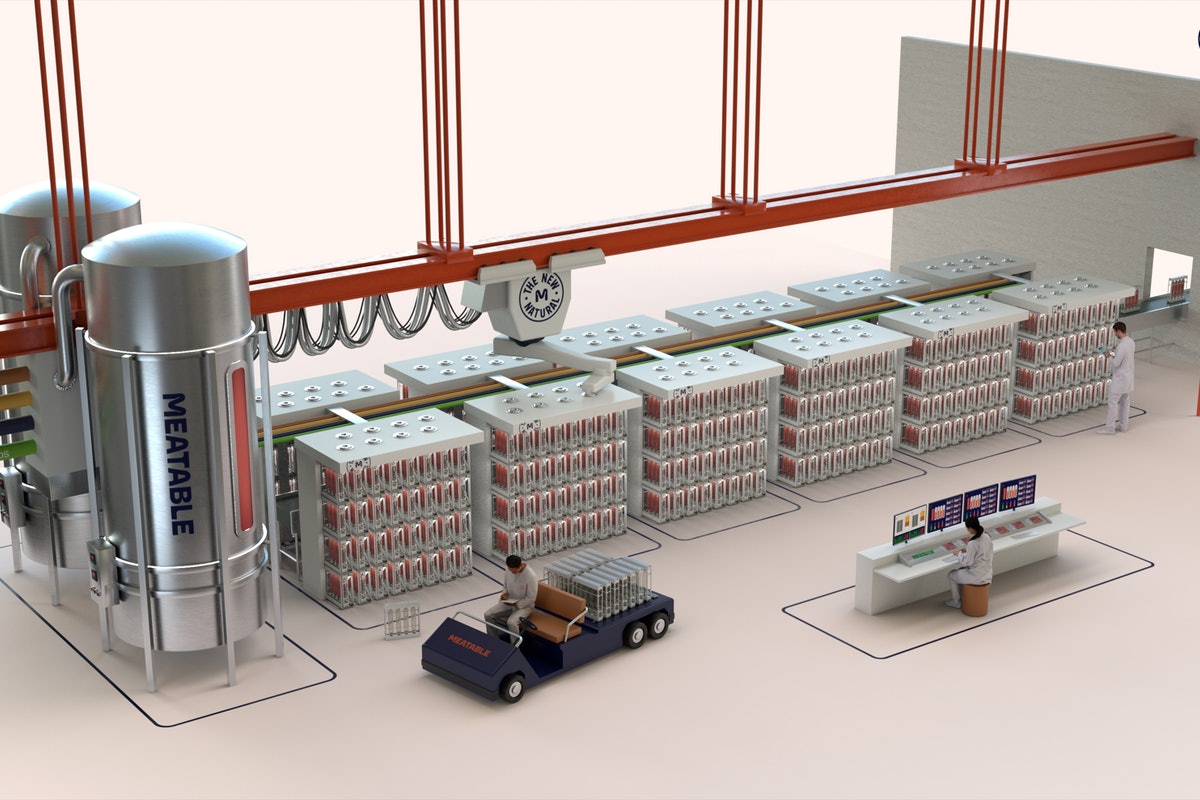

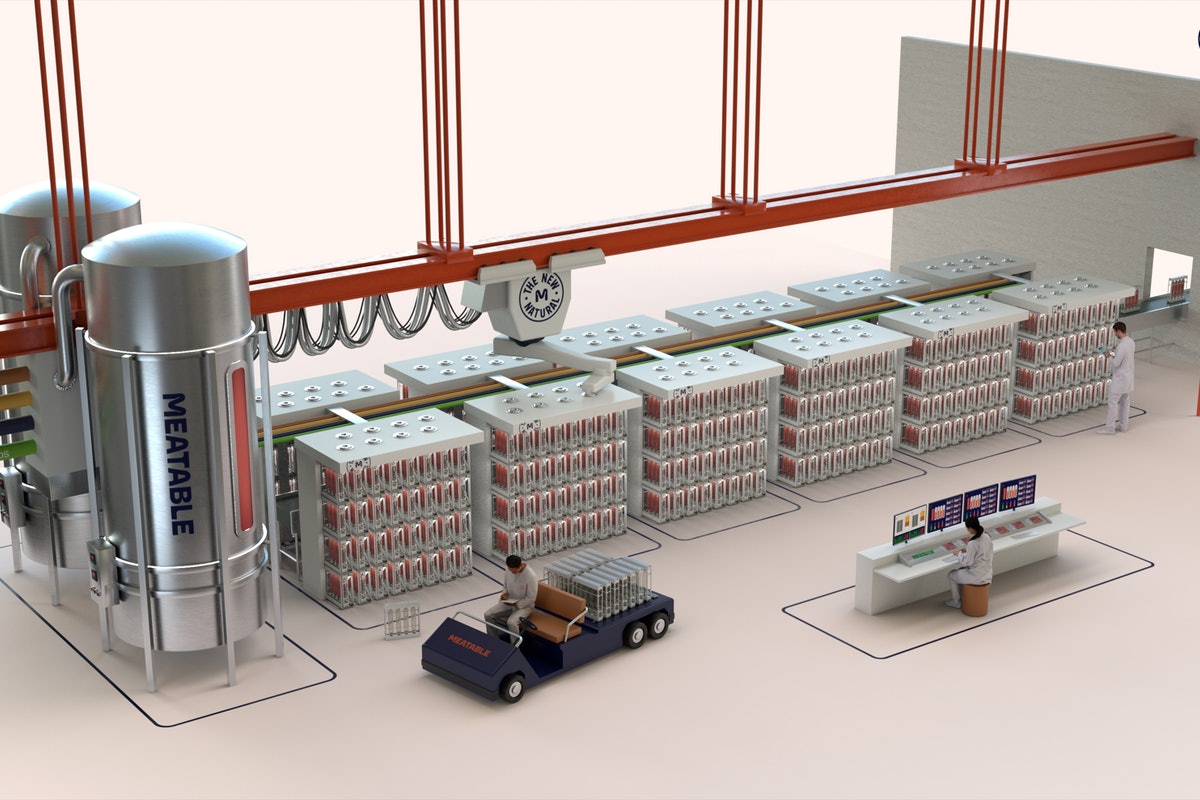

Cultivated meat takes the mimicry to another level. At Meatable, the process begins by extracting a single cell sample from a cow or pig. The cell is then cultivated in a bioreactor, where it’s fed various nutrients. These elements are mixed and shaped to produce the finished meat.

One ingredient Meatable doesn’t use is fetal bovine serum (FBS), a common growth medium in cultivated meat. FBS is harvested from cattle fetuses after their mothers are slaughtered. In addition to tainting the “cruelty-free” marketing of cultured meat, the substance is extremely expensive to use.

Instead of FBS, Meatable harnesses pluripotent stem cells, which can multiply indefinitely and convert into almost any cell type. These pluripotent cells replicate the natural growth of muscle and fat — two essential ingredients to make meat taste like meat.

Meatable first induces a single cell from a just-born animal’s umbilical cord, which is collected without causing any harm. The company’s proprietary OPTi-OX system then rapidly converts the pluripotent cells into the desired muscle and fat cells.

Luining compares the technique to brewing beer in a vat.

“We’re feeding the cells, brewing to create more cells, and then we turn them into muscle or fat,” he says. “This is basically what meat consists of. It’s the cells of the animal — it is actual meat.”

This puts my head in a spin. It’s not vegetarian, but if it’s removed every drawback of conventional meat, why wouldn’t I eat it? And why can’t I find it in Europe?

Going Dutch

Meatable’s home country, the Netherlands, is often referred to as the birthplace of cultivated meat. In 1948, a Dutch medical school student researcher, Willem van Eelen, came up with the idea after stumbling across experiments using stem cell tech to grow cells in a tank. He wondered if similar techniques could cultivate meat.

Van Eelen went to file several patents that sought to make his vision a reality, but struggled to raise enough money to pursue his plans. He did, however, lay the foundations for another milestone in the Netherlands.

In 2005, Van Eelen helped convince the Dutch government to fund research into cellular agriculture. The program prompted Mark Post, a professor at Maastricht University, to develop the first cultivated hamburger. His achievement attracted mainstream media attention, and turned many of Van Eelen’s doubters into believers.

In 2013, Post formed his own biotech startup, the Netherlands-based Most Meat. His work has also inspired numerous scientists, including Luining.

Meatable, however, plans to launch its products in Singapore — and with good reason.

Singapore already has cultivated meat on the market. In 2020, the country’s food agency became the first regulatory body to approve the sale of a lab-grown meat product: chicken developed by Eat Just, a Californian startup.

The city state’s embrace of cultured meat is rational. Just 1% of its land is available for agriculture, which forces Singapore to import more than 90% of its food. To shore up against global food supply shocks, the country aims to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030. Cultured meat offers the opportunity to maximize the island’s scarce farming resources.

Meatable will enter the market in partnership with Esco Aster, the world’s only licensed cultivated meat manufacturer. The duo this week unveiled plans to bring cultivated pork to Singapore restaurants in 2024, and supermarkets by 2025.

Singapore’s regulatory landscape, diverse population, and openness to emerging technologies have created an attractive test ground for cultured meat. Meatable hopes it provides a launching pad for global expansion.

“Let’s see if we can get it into different jurisdictions,” says Luining. “It’s all about practice, because doing this is pioneering work.”

In Europe, however, the path to regulatory approval is a long one.

The EU must provide approval before any cultivated meat is sold in the union. The bloc’s regulatory requirements are typically clearly defined, but time-consuming to meet.

Still, there are encouraging signs from the union. In 2021, the REACT-EU program gave another Dutch company, Mosa Meat, €2 million to cut cultured beef costs, while Horizon Europe offered €32 million for research into sustainable proteins. The European Commission also recently funded lab-grown foie gras.

The Netherlands, meanwhile, is increasing domestic support. In March, the Dutch government passed a motion to legalize public samplings of cultured meats. Four months later, Meatable’s founders finally tasted their first product: pork sausages.

Funding has also increased. In April, the Dutch government allocated €60 million for the development of cellular agriculture. The grant was the largest ever sum of public funding for the sector.

These moves have attracted global recognition. ProVeg International, an NGO dedicated to reducing animal consumption, recently named the Netherlands the top European nation for government support of cultured meat.

The country may have lost its head-start in the sector, but it’s starting to catch up again.

Global divides

Legislation isn’t the only barrier to mainstream adoption. Cultivated meat remains costly to produce, complicated to scale, and ethically contentious.

Scientists have also questioned the environmental benefits. A 2019 study from Oxford University determined that, in some scenarios, cultivated meats released more greenhouse gasses than conventional farming.

Research published last year produced more positive conclusions. Analysts at CE Delft found that renewable energy could lead cultivated meat to compete on costs with conventional meat production by 2030 — and leave a lower carbon footprint. Critics, however, called the predictions unrealistic.

The field also has powerful rivals. The value of the global meat sector was estimated at $897 billion in 2021, and forecast to reach $1.354 billion by 2027. The industry’s farmers and lobbyists have a lot to lose from a transition to lab-grown meat.

Cultured meat must also overcome a range of consumer concerns, from religious objections to Gen Z viewing the produce as disgusting.

These challenges may not prove insurmountable. Public opinions can be swayed; bigger bioreactors, cheaper nutrients, and increased cell densities can yield efficiency surges.

Luining is confident that Meatable will sell a cost-competitive product by 2025. Ultimately, he envisions consumers mixing conventional, cultured, and plant-based meat.

He makes one more surreal appeal to my vegetarian diet. “You could have a steak while the cow whose cells it’s been made from is sitting next to you happily living its life.”

Luining ends our chat with a question: would I eat his cultivated meat?

If the cow next to me has no beef with it — why not?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24077319/RE57ifo.jpeg)